紐澤西RMANJ的 次世代定序NGS研究 nextgen CCS新鮮胚胎植入的時代已經來臨,而冷凍胚胎時代已經過去

2015.02.26

紐澤西RMANJ的 次世代定序NGS研究 nextgen CCS新鮮胚胎植入的時代已經來臨,而冷凍胚胎時代已經過去

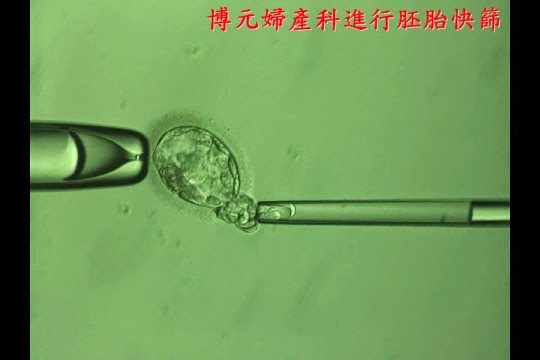

.jpg)

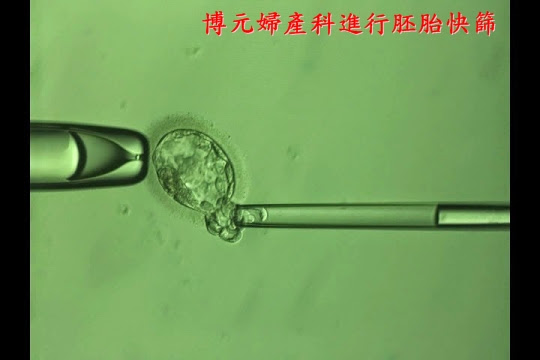

.jpg)

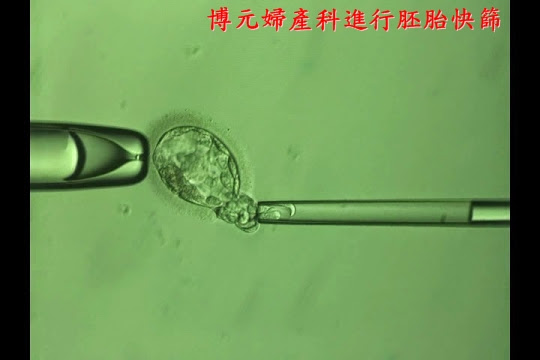

.jpg)

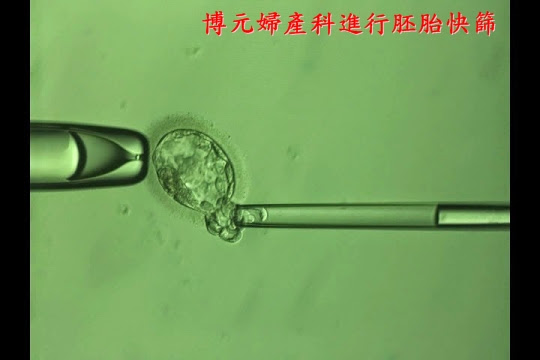

.jpg)

在2014年去年2月10日首先RMANJ他們進行了一個200

這是一個雙盲的研究,實驗組是植入兩個經過次世代定序的胚胎,

而對照組是外觀選擇的胚胎,

次世代無疑它的好處是快速,

最重要的是很便宜,

在之前紐澤西團隊他們是是用qPCR來進行胚胎切片,獲得84.

他們仍然認為CCS應該可以

更精準或更便宜,

所以在去年2月進行了一個次世代定序的臨床研究,

有關RMANJ紐澤西團隊他們在1999年成立至今,

已經誕生3萬個試管寶寶,

在2013年美國生殖醫學會有發表28篇的學術論文,

他們最為人稱讚的是不斷的開發新的技術,

使用qPCR24染色體選胚胎植入胚胎:快速新鮮胚胎植入,

所以他們最近在美國不孕症與醫學期刊發表一份看法就是,

基於7個理由(ref):CCS新鮮胚胎植入的時代已經來臨,

RMANJ試管嬰兒中心更奇怪和有趣的觀察是,

他們不使用a-CGH去進行胚胎篩檢,

而從SNP跳到qPCR再跳到NGS,

而直接跳過a-CGH,

這真的很值得玩味的一個發現,是不是代表a-CGH:

(1)它在篩檢胚胎太過精準以至於會"誤棄"胚胎。

(2)會不會是太繁瑣要冷凍胚胎,

a-CGH的晶片費用非常的昂貴,

我們持續觀察美國紐澤西團隊次世代定序這200個研究NGS

應該會優於qPCR的84.7%的活產率 報告。

REF::

CCS不必冷凍胚胎,如王寶釧苦守寒窰18年等報告!qPCR

CCS 新鮮胚胎植入的 "7大" 理由,根據RMANJ紐澤西團隊斯考特Scott的論述,

(1)

(2)提高試管嬰兒成功率是最大的考慮,

(3)因為CCS的費用實在是很昂貴,

(4)使用CCS可以減少多胞胎的比率,

(5)冷凍胚胎其實是不可以不用的,

(6)有一些病人並不能從CCS得到好處,只有部分的病人,

(7)能夠進行CCS一定要:

1.進行囊胚期胚胎培養、

2.能夠進行胚胎切片、

3.能夠進行快速冷凍的方法。

因此這三大要件都存在的實驗室,才能夠進行CCS新鮮胚胎植入,

也因此

進行胚胎全基因放大檢測胚胎的染色體,

進行胚胎的植入"新鮮"胚胎植入,

參考:

Comprehensive chromosome screening with

synchronous blastocyst transfer: time for a

paradigm shift*

Recently, the nature of assisted reproductive technology

(ART) laboratory investigation has been shifting. Tradition-

ally, it has focused on optimizing the culture milieu or assur-

ing fertilization; now, a variety of new technologies are

available to assess the reproductive potential of individual

embryos. Perhaps most prominent has been the resurgence

of embryonic aneuploidy screening. The validation of

24-chromosome testing platforms has led to a variety of

studies demonstrating higher implantation and delivery rates.

These findings are now translating to changes in the para-

digm of ART practice.

Caution is prudent in times of change, and methodical

analyses are needed. Evaluation logically focuses on efficacy

in terms of enhanced implantation and delivery rates. Other

factors, such as safety, cost, and accessibility also deserve

thoughtful consideration. Evaluations of these endpoints

should take into account the caliber of the data supporting

the ‘‘new paradigm,’’ in parallel with the data supporting

the current ‘‘standard of care,’’ and both should be evaluated

with the same level of rigor.

Several investigators have recently expressed concerns

about the implementation of comprehensive chromosomal

screening (CCS) in clinical practice. Fortunately, an ever-

growing literature is available to provide clinicians and scien-

tists with the information they need to evaluate many of the

critical issues. Some of the major issues and questions

include:

1. Efficacy of 24-chromosome embryonic aneuploidy

screening. Multiple studies provide class I data demon-

strating higher implantation and delivery rates following

24-chromosome aneuploidy screening. In distinct contrast

to fluorescent in-situ hybridization-based preimplantation

genetic screening studies in which every randomized

controlled trial (RCT) showed either no improvement or

active detriment, every RCT involving 24-chromosome

screening has demonstrated benefit (1–3).

2. What magnitude of improvement in clinical outcomes is

necessary to justify screening? Answering this question

inevitably involves a subjective decision that will be

made by patients after counseling by the clinicians caring

for them. Given that aneuploidy rates vary from 25% in

women in their late twenties to 85% for those in their

mid-forties, the opportunity for enhancing outcomes will

be greatly affected by the age of the female partner and

her intrinsic ovarian responsiveness. It is unlikely that im-

provements will be made in direct proportion to the aneu-

ploidy rate, as many other factors affect delivery rates.

Women with high embryonic arrest rates are unlikely to

attain the full benefit of screening. Still, the magnitude of

the enhanced outcomes seen in the RCTs is substantial.

3. The cost of CCS may be burdensome. Although substantial

costs are associated with CCS, even in proportion, they are

* This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (http:// would appear that this type of screening is appropriate

660 VOL. 102 NO. 3 / SEPTEMBER 2014

lower than the costs of additional ART cycles. A definitive

cost-effectiveness study has not been published to date.

Although enhanced delivery rates should translate to fewer

treatment cycles, that question must await more detailed

analyses before conclusions may be drawn. Additionally,

savings attributable to decreased pregnancy losses and the

care provided to ongoing aneuploid gestations would need

to be considered. Given that, and the impact on transfer or-

der discussed below, it is unlikely that cost effectiveness will

limit implementation of embryonic aneuploidy screening.

4. Implementation of CCS may actually increase the risk for

multiple gestations unless transfer order is reduced. That

very fact has already been established in a randomized

controlled trial (2). In fact, it is a mathematical certainty.

As implantation rates increase, if there is no decrease in

transfer order, then multiple gestation rates will inevitably

rise. However, it is not reasonable to assume that transfer

order would remain the same. For the first time, there are

class I data demonstrating eSET after CCS is as effective

as double-embryo transfer of unscreened embryos (2).

All prior RCTs comparing elective single-embryo transfer

(eSET) versus double-embryo transfer found poorer per-

transfer outcomes with eSET. If CCS is used, that is no

longer true. Equivalent delivery rates are maintained while

virtually eliminating the risk of twins. The paradigm using

CCS and eSET produced an average gain in birth weight of

approximately 650 grams. No other single intervention in

obstetrics has produced such a dramatic enhancement in

birth weight, which is known to be highly correlated

with the health of the child. Of course, the transfer of

two screened embryos would further increase pregnancy

rates, but at the cost of quite elevated twin rates; thus, it

should be discouraged. Armed with these data, utilization

of eSET in our program has risen from less than 6% to

approximately 60% over a 4-year interval.